Uniting a Pacific Legacy

The Polynesians, the group of Indigenous peoples encompassed by the geographic boundaries of Hawai'i to the north and New Zealand and Rapa Nui to the east, have been navigators across the expanse of our oceans since the time of our ancestors. Venturing forth, they made their homes on many of the islands of the Pacific. These ancient journeys hinged upon a profound grasp of celestial patterns, wind currents, ocean swells, and other subtle indications of navigation made by nature itself.In the ‘70s, a resurgence of Native Hawaiian cultural heritage began to take root throughout the Hawaiian Islands, signifying a "Native Hawaiian Renaissance". Cultural practitioners worked collaboratively to rejuvenate traditional Hawaiian customs around agriculture, reforestation, the arts, music, dance, language and the ancient craft of wayfinding by celestial navigation. It was during this time of cultural revitalization that the Polynesian Voyage Society (PVS) was established in 1973. United by a shared vision, its three founding members, Dr. Ben Finney, an esteemed anthropologist, Herb Kawainui Kane, a Hawaiian artist, and Tommy Holmes, an author, hoped to perpetuate the artistry and scientific knowledge associated with traditional Polynesian seafaring and the intrepid spirit of discovery. But before they could set sail, they needed a boat — a traditional canoe.

(Diagram of Hōkūlea developed by Herb Kawainui Kane)

The three embarked on a mission to create a traditional Hawaiian canoe from the accounts of generations past, and subsequently navigate the Pacific relying upon traditional voyaging methods sparked a fascination with cultural revitalization. Kane created an initial blueprint for the canoe while simultaneously crafting a painting to display what the completed product would look like, exhibiting it in Honolulu to garner financial support. The exhibition attracted not only donors but also volunteers who offered their resources, skills, and the gift of their time. The vessel was constructed over several years and launched in 1975. Kane and his fellow navigators embarked on a maiden voyage, reacquainting themselves with the wisdom of their ancestors as they navigated the seas.

The canoe was named Hōkūlea, meaning "star of gladness" in the native Hawaiian language, and was inspired by Arcturus, a celestial body that seemingly traverses directly overhead at the latitude of Hawai'i.

(Painting depicting Hōkūle’a by Herb Kawainui Kane)

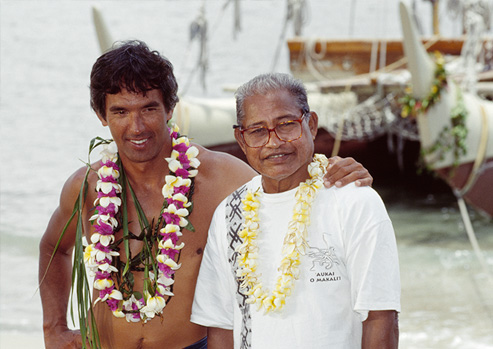

(Nainoa Thompson (left) and Mau Piailug (right) in 1998)

Prior to the construction of Hōkūle’a, the Polynesian Voyage Society (PVS) sought a master Polynesian navigator to guide them. In their pursuit to revive the long-lost art of Native Hawaiian wayfinding, Nainoa Thompson hoped to find a master navigator to teach aspiring traditional navigators. He eventually convinced Mau Piailug from Satawal in the Federated States of Micronesia, to defy tradition and impart the wisdoms of wayfinding without relying on instruments to someone outside of their community. Together, they charted the maiden voyage of Hōkūle’a to Tahiti and back to Hawai’i in 1976. Through this remarkable journey, Thompson emerged as the first Hawaiian since the 14th century to practice the ancient art of wayfinding.

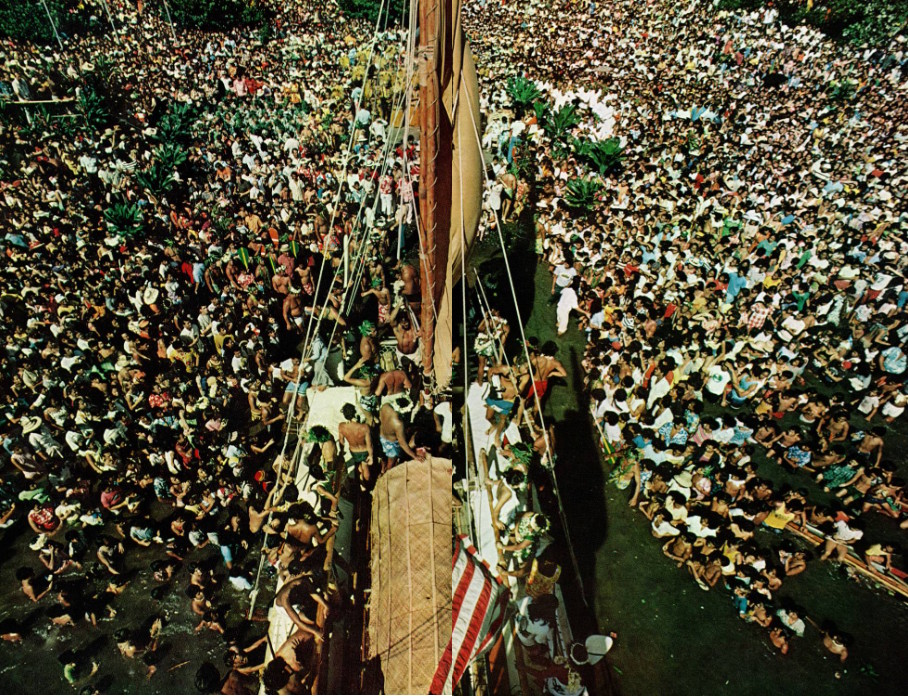

(Hōkūle’a arriving in Tahiti, 1976)

(Hōkūle’a returning to Oahu from Tahiti in 1976)

The Search for a Canoe’s Heart

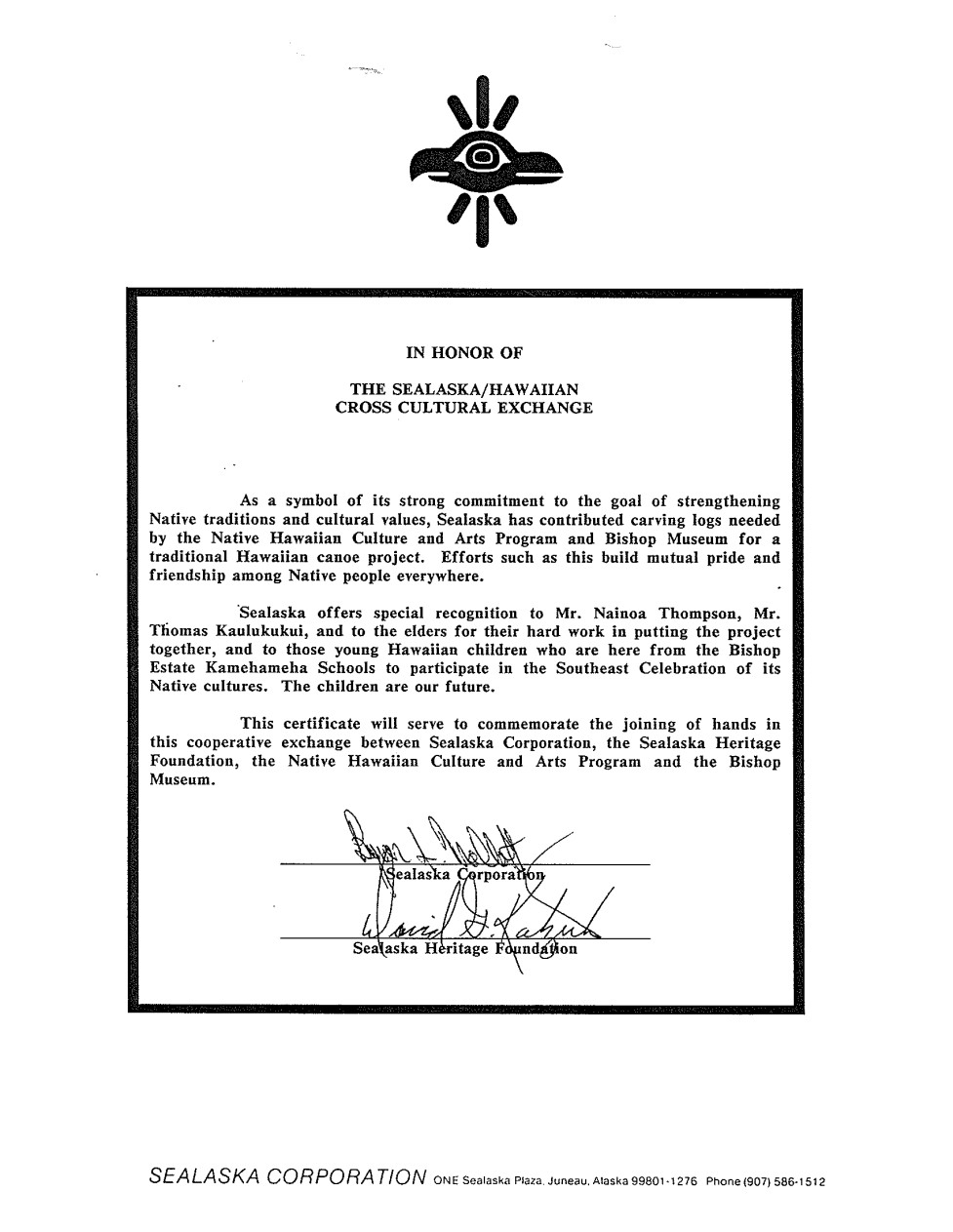

Thompson and a group of other PVS navigators, now that they had learned the necessary skills to navigate traditionally, faced another challenge: the construction of another vessel made from resources available in Hawai’i. This ambitious endeavor spanned five years and led to the deep relationship between Sealaska and PVS. It is recounted that

(Official document of Sealaska/Hawaiian cross-cultural exchange)

The Polynesian Voyage Society, hoping to construct an authentic Hawaiian voyaging canoe from traditional materials, faced a barrier with regards to resources. Koa trees, the resources utilized by their forebears to construct canoes, were scarce. By the 1990s, the Hawaiian forests had been depleted to such an extent that locating trees of sufficient size was next to impossible. From this challenge, the connection between Sealaska and the Polynesian Voyaging society was born.

Upon hearing of the situation, Tlingit Elder Judson Brown and Sealaska President and CEO Byron Mallott offered PVS two sizable Sitka spruce logs to build the canoe hulls. The logs were sourced from Shelikof Island, specifically Soda Bay on Prince of Wales Island and served as the foundational materials for the construction of the Hawai’iloa.

The name Hawai‘loa pays homage to the renowned Polynesian voyager Hawai‘iloa, who, according to one account, is credited with the discovery of the Hawaiian Islands and is revered as the common ancestor of all Hawaiians.

This remarkable vessel traversed both the waters of Southeast Alaska and the South Pacific, embodying the spirit of ancestral exploration, cultural exchange, and reciprocity everywhere she sailed.

(Former CEO, Byron Mallot learning Hula aboard the Hawai’iloa on the way to Haines)

Over the years, Sealaska and representatives from diverse Indigenous Hawaiian groups have continued this reciprocal relationship, engaging in constructive dialogues as we share collective goals concerning the well-being of our oceans and the stewardship of our global environment. This enduring relationship with Hawaiian Indigenous communities traces its origins back three decades growing stronger by the year despite the over 2000 miles of open sea that separates us.

“Continuing to strengthen our relationships with our Hawaiian relatives and other Indigenous people is critically important to Sealaska as we collectively look to our shared future.

The Hawaiian and Tlingit, Haida, and Tsimshian people have a deep connection with other ocean and canoe people — we are are all deeply tied to the environment.”

- Anthony Mallott (CEO of Sealaska)

(Executive leaders of ʻAha Moananuiākea and Sealaska in front of Hawaiʻiloa (in drydock), Hoʻoilina Conference, 2019.)

For additional information on Polynesian Voyage Society and the Moananuiākea Voyage, visit www.hokulea.com or follow @hokuleacrew on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, and YouTube.

To learn more about Sealaska’s historical relationship with Polynesian Voyage Society, explore the links below:

A Voyage for Earth: This chapter follows the preparation and launch of the Moananuiākea Voyage, an ambitious journey of three canoes with a mission to unite Pacific communities and inspire a global education campaign centered on indigenous knowledge and ocean stewardship.

Regional Sailing Plan:Follow Hokulea as PVS voyages an estimated 43,000 nautical miles around the Pacific, visiting 36 countries and nearly 100 indigenous territories.

Birth of Hawai’iloa: This chapter follows the story of the creation of Hawai’iloa, the symbolic voyaging canoe that embodies the spirit of Polynesian exploration and the mission to care for the Earth.

Power of Cultural Exchange: This chapter highlights the enduring relationship between Hawai’i and Alaska Native communities, the ceremonies and traditions that connect them, and the lessons we continue to learn from one another.

Key Leaders Inspiring Generations: In the final chapter, the focus is on our ancestors that, to this day, continue to guide us with wisdom and deep belief in the traditional values of our people.